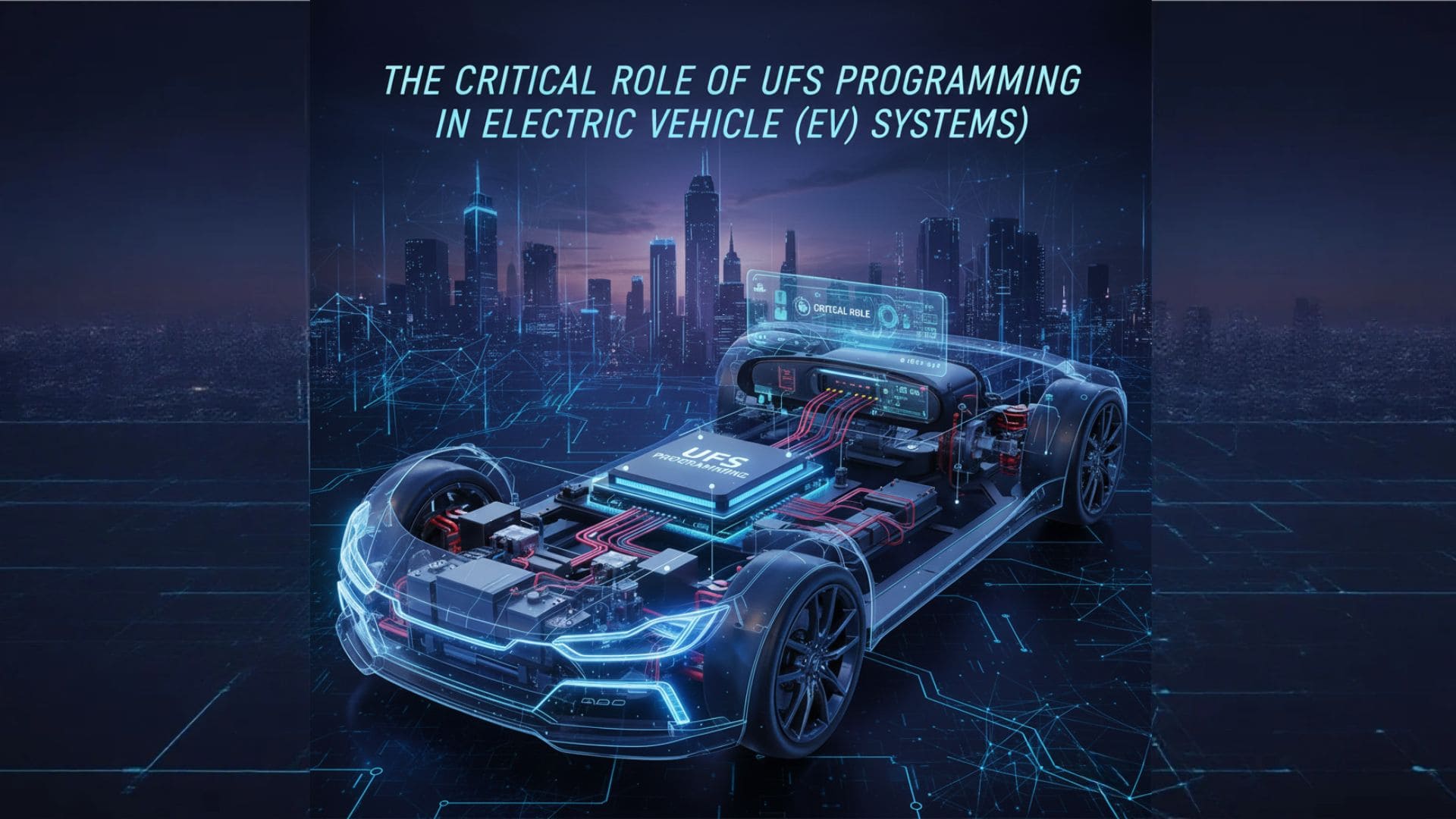

The electronics manufacturing sector is currently navigating a significant transition driven by the demand for higher data capacities. As the industry moves toward the post-pandemic "AI era," the complexity of firmware has scaled exponentially. From electric vehicle (EV) infotainment systems using UFS (Universal Flash Storage) to smart home appliances relying on eMMC, the volume of data that must be pre-programmed into each integrated circuit (IC) has surged from megabytes to hundreds of gigabytes.

This data explosion has turned the programming stage into a critical production bottleneck. In many manufacturing facilities, the programming process is no longer a peripheral step but a primary factor determining Total Cycle Time (TCT). When the programming speed cannot match the SMT (Surface Mount Technology) placement speed, the entire production line faces costly idle time.

Key bottlenecks often identified in modern production lines include:

For production managers, identifying whether the bottleneck is hardware-bound (speed of the programmer) or process-bound (manual handling) is the first step in calculating a meaningful Return on Investment (ROI) for automation.

Manual programming remains a common practice for small-batch prototyping and low-complexity projects. However, as production scales toward mass manufacturing, the inherent limitations of human-operated stations become significant liabilities. The primary constraint is not just speed, but process consistency.

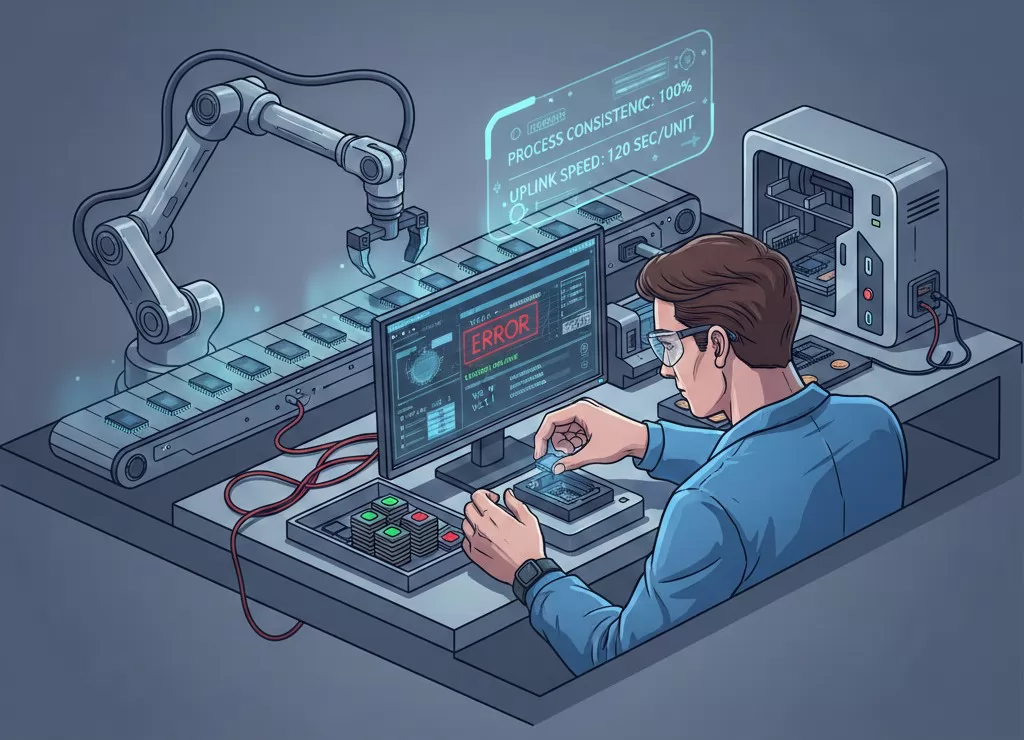

In a manual setup, an operator must physically pick an IC, orient it correctly into a socket, initiate the software sequence, and then move the programmed chip into the output tray. This cycle introduces several technical risks that can compromise the ROI of a production line:

Furthermore, the Human Duty Cycle is inherently inefficient for high-density devices. If a UFS chip takes 120 seconds to program, a manual operator is either idle during the burn-in or must manage multiple independent programmers simultaneously—a scenario that drastically increases the likelihood of operational mistakes.

The transition from manual to automated programming is not merely a change in logistics; it is a fundamental shift in hardware architecture. Modern automated systems, such as the AST Series, are engineered to handle the throughput requirements of high-density flash memory through advanced FPGA (Field-Programmable Gate Array) architectures.

Unlike general-purpose controllers, an FPGA-based programming core allows for hardware-level parallelization. This means the system can execute high-speed signal timing precisely tailored to the specific requirements of UFS or eMMC protocols. This architecture minimizes the "dead time" between command cycles, ensuring that the chip is programmed at its maximum theoretical write speed.

The mechanical precision of an automated handler is equally critical. Key architectural features include:

By integrating 20 years of software innovation with robust hardware design, these architectures provide a deterministic environment where programming time is predictable and human-induced variables are removed from the equation.

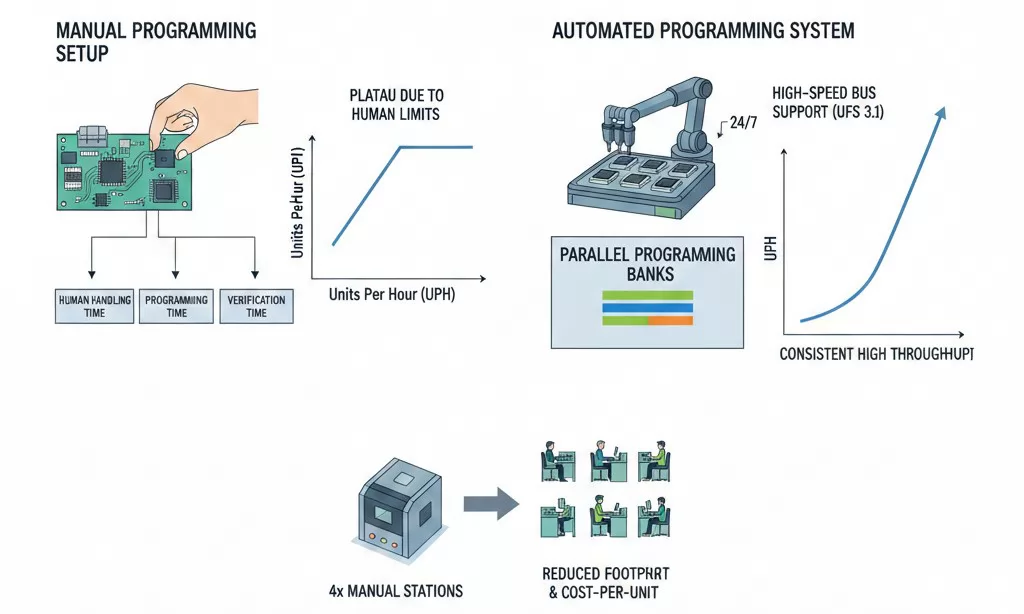

When calculating ROI, Units Per Hour (UPH) is the most critical metric. The throughput gap between manual and automated programming widens significantly as device density increases. For high-density storage components like UFS 3.1 or large-capacity eMMC used in automotive and smart home sectors, the sheer volume of data makes manual throughput mathematically unsustainable for mass production.

In a manual setup, the total cycle time is the sum of Human Handling + Programming Time + Verification Time. Because these steps are sequential and limited by human physical speed, the UPH typically plateaus quickly. In contrast, automated systems utilize parallel processing to decouple handling time from programming time.

Consider the technical advantages of automation for high-density devices:

For a production line moving 1,000 units per day of 64GB eMMC, an automated system can often reduce the required "programming footprint" from four manual stations down to a single compact machine, drastically reducing the cost-per-unit.

The most immediate financial impact on the ROI of an IC programming line is the reduction of direct labor costs. In a manual programming environment, the labor cost is a variable that scales linearly with volume: more chips require more operators, more workstations, and more floor space. Automation transforms this into a fixed-cost model.

However, the calculation goes beyond simple hourly wages. To find the true ROI, manufacturers must account for the "Hidden Costs of Human Error":

The Multiplier Effect: By replacing four manual operators with one automated system, a company not only saves on four salaries but also reduces the management overhead, recruitment costs, and the physical footprint of the production floor, often resulting in a hardware payback period of less than 12–18 months for high-volume lines.

In the world of high-precision electronics, a "working" chip is not enough; it must be a "reliable" chip. Yield Loss at the programming stage is a silent ROI killer. When a manual operator handles a high-density eMMC or UFS device, the risk of micro-damage is significantly higher than most manufacturers realize.

Automated systems improve yield rates through three technical pillars:

By increasing the First Pass Yield (FPY), manufacturers avoid the cascading costs of scrapping a fully assembled PCBA simply because of a programming-induced defect. For high-value automotive or industrial boards, saving just a few boards per month from the scrap bin can pay for the automation upgrade itself.

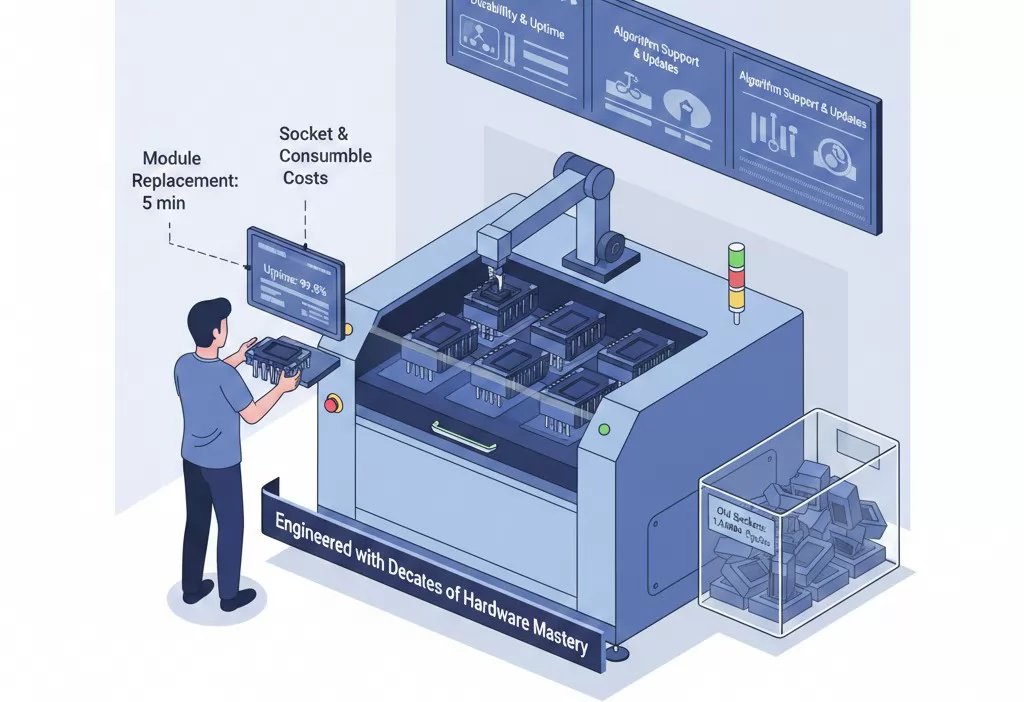

When evaluating the ROI of IC programming, focusing solely on the initial purchase price is a common oversight. A true financial assessment requires looking at the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) over a 5-to-10-year horizon. This is where the distinction between "budget" equipment and systems built on decades of hardware mastery becomes evident.

For a production line to remain profitable, the programming infrastructure must balance three TCO variables:

Maintenance Predictability: High-quality automated systems are designed for ease of maintenance. Modular "plug-and-play" programming sites allow for servicing without shutting down the entire machine, ensuring that production continues even during routine calibration or socket replacement.

In the modern digital manufacturing landscape, hardware is only as capable as the software that drives it. For high-density devices like SPI Flash and UFS, the "software genius" behind the programmer determines how quickly a new product can move from the R&D lab to the mass production floor. Manual programming often relies on fragmented, standalone software that requires manual data entry—a significant risk factor for version control errors.

Automated programming systems provide a unified software ecosystem that offers several ROI-enhancing advantages:

By leveraging 20 years of software development experience, these systems reduce the "setup time" for new projects. In an industry where Time-to-Market (TTM) can determine a product's success, the ability to rapidly configure and deploy a new programming cycle is a major competitive asset.

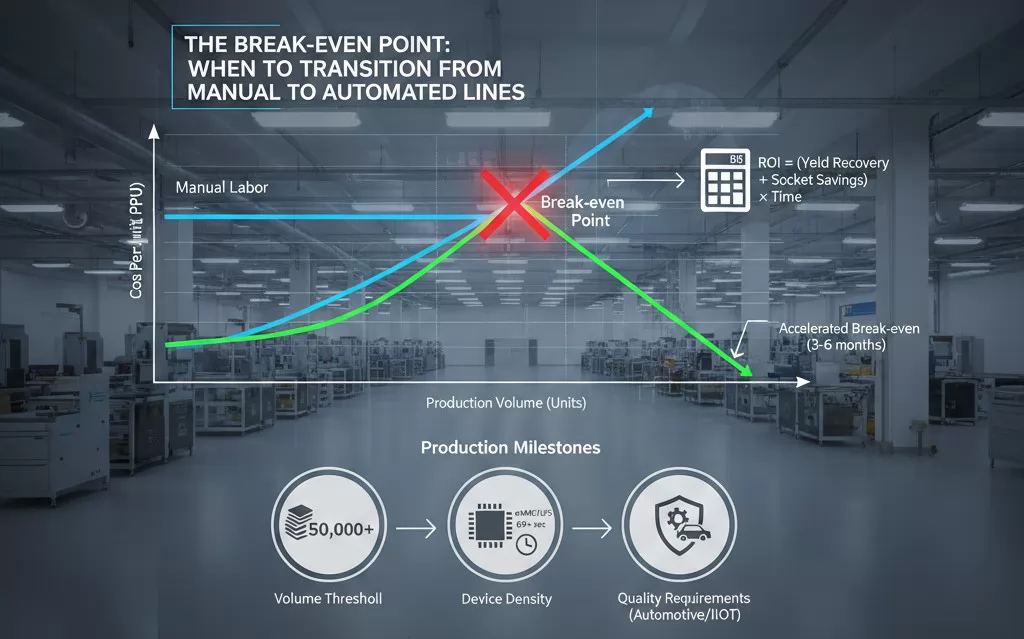

For many production managers, the ultimate question is not if to automate, but when. Calculating the break-even point involves comparing the Cost Per Programmed Unit (CPPU) of manual labor against the amortized cost of an automated system. While manual programming has low upfront costs, its CPPU remains high and constant; conversely, automation has a higher initial investment but a CPPU that drops drastically as volume increases.

Typically, the transition is triggered by three specific production milestones:

ROI Calculation Tip: When presenting the case for automation to stakeholders, include the "Yield Recovery" and "Socket Savings" identified in previous chapters. Often, these two factors alone can accelerate the break-even point by 3–6 months.

The rapid advancement of AI and the proliferation of smart home ecosystems are fundamentally changing the requirements for electronic components. As devices become "smarter," they require larger firmware footprints to handle edge computing and localized AI processing. Investing in an automated programming solution today is not just about solving today's bottlenecks; it is about future-proofing your production line for the next decade of innovation.

A future-ready production line must be capable of adapting to several key trends:

By choosing a partner with a deep legacy in both hardware mastery and software innovation, manufacturers ensure that their programming capabilities will grow alongside the technology they produce. Systems like the AST Series represent this pinnacle of automation—designed for ultra-fast, flawless execution that makes high-volume programming as effortless as the air around us.

Velomax is a brand built on a foundation of technical excellence and user-driven innovation. With over 10 years of hardware design mastery and 20 years of software development genius, Velomax elevates IC programming into a new era of "aero-speed" performance. In a global landscape reshaped by AI and digital transformation, we specialize in high-speed programming solutions for the most demanding high-density devices, including UFS for electric vehicles, eMMC for smart appliances, and SPI Flash for industrial equipment.

Hardware Mastery: A decade of experience delivering robust, reliable, and industrial-grade high-speed programmers.

Software Genius: Two decades of innovation ensuring seamless automation, precision, and integration across all platforms.

The AST Series Advantage: Our next-gen automated systems, powered by the AeroSpeed Series and advanced FPGA architecture, deliver unmatched speed and precision for flawless production execution.

Discover this amazing content and share it with your network!

Your Name*

Your Email*

*We respect your confidentiality and all information are protected.