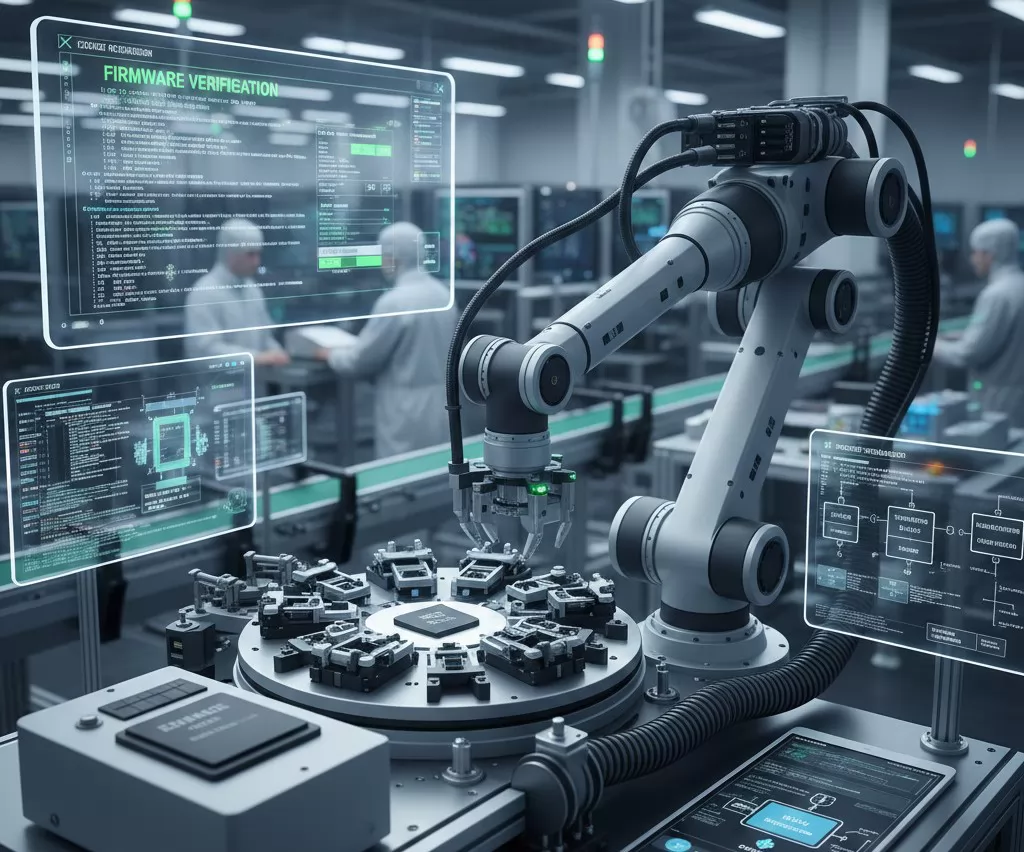

Integrated Circuit (IC) programming is the process of loading specific machine code or configuration data onto a blank semiconductor chip, which dictates the chip’s function and behavior within an electronic system. Without this critical step, most programmable ICs—whether they are memory, microcontrollers, or logic devices—are essentially inert.

In simple terms, programming is the act of giving the chip its instructions. This process is fundamental to electronics manufacturing, bridging the gap between hardware design and software execution. The process involves writing digital data (usually in the form of a binary file, often a $.hex$ or $.bin$ file) into the non-volatile memory area of the chip.

Programming_1765182360_WNo_1024d771.webp)

A functional electronic device relies on two primary components being correctly matched:

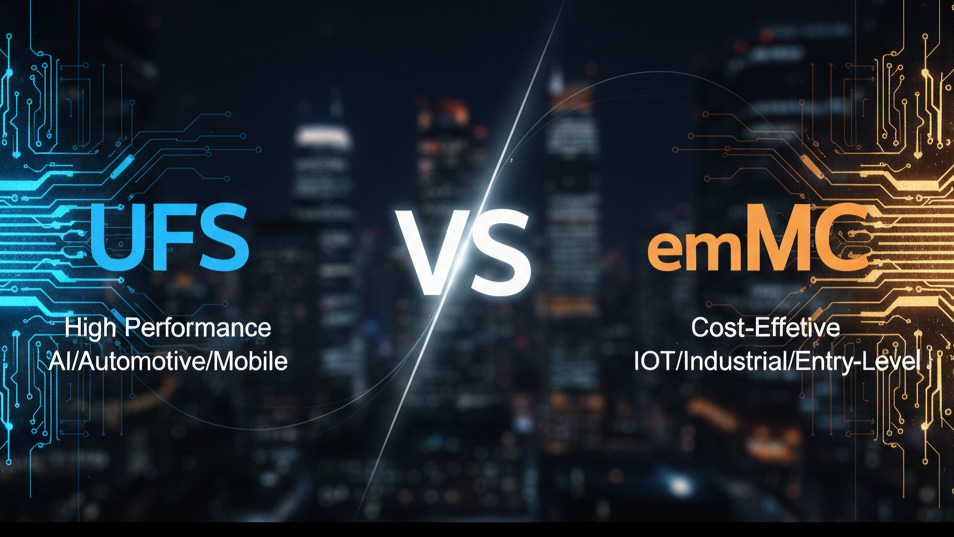

The complexity of this programming step scales dramatically with the density and type of the device. For high-speed applications, especially those using modern high-density memory like UFS and eMMC, the speed, accuracy, and verification of the programming process are absolutely vital for mass production yield.

IC programming is not merely a technical step; it is a critical process point that dictates product differentiation, quality control, and manufacturing efficiency. In a high-volume production environment, flaws introduced during the programming phase can lead to catastrophic yield loss and costly rework.

The programming stage serves several essential roles:

As electronic devices become more complex—driven by technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), Electric Vehicles (EVs), and advanced computing—the size of the required firmware files has exploded. Devices like UFS (Universal Flash Storage) and high-capacity eMMC memory can store gigabytes of data.

This increased density introduces new manufacturing challenges:

For large-scale industrial operations, the programming solution must therefore focus equally on speed and precision to keep pace with demand and maintain competitive costs.

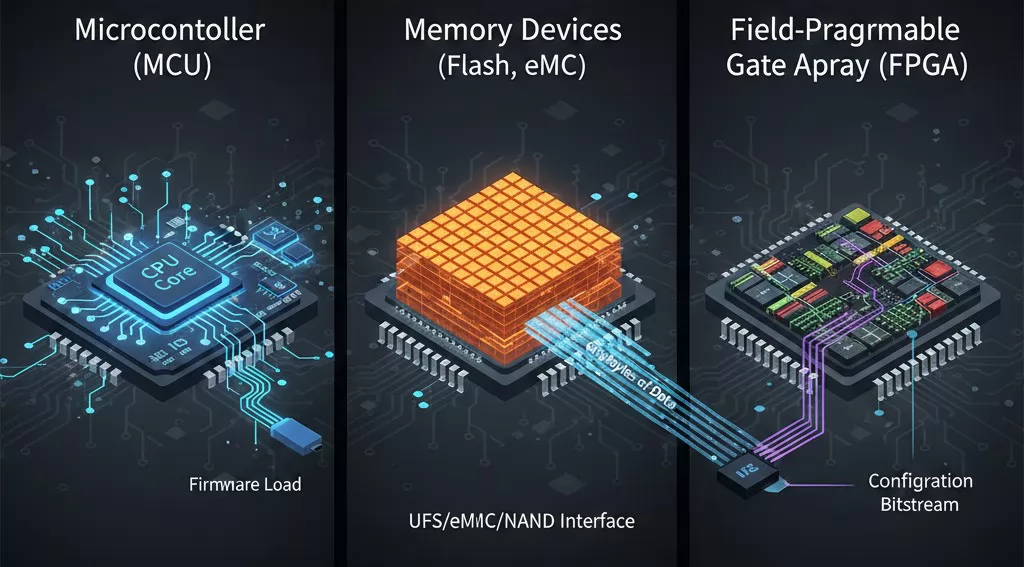

The term "IC programming" applies to a wide range of devices, each with distinct architectures and programming requirements. Understanding the differences between these device types is crucial for selecting the appropriate programming hardware and software settings.

While the market is diverse, most programmable ICs fall into three main categories based on their primary function:

MCUs are essentially small, self-contained computers on a single chip. They integrate a CPU core, memory (both volatile RAM and non-volatile Flash/EEPROM), and input/output peripherals. Programming an MCU typically involves loading the application's firmware into its internal non-volatile memory block. This firmware includes the operating system, device drivers, and core application logic.

These devices are designed primarily for data storage. They are found in almost every electronic product, storing everything from bootloaders to massive user data files (e.g., in smartphones, SSDs, and smart appliances). The trend here is toward higher density (gigabytes) and faster interfaces (e.g., UFS and eMMC), demanding high-speed programmers capable of handling complex protocols and massive data throughput to avoid production bottlenecks.

FPGAs represent a different form of programming. Unlike MCUs that run software, FPGAs are hardware structures that are reconfigured to perform specific logic functions. Programming an FPGA involves loading a configuration bitstream into its internal memory, which physically re-wires the logic gates and interconnections. This allows for parallel processing and highly optimized custom hardware acceleration, common in telecom and specialized computing.

The method used to communicate with the chip during programming—the protocol—varies significantly:

Manufacturers typically choose between two fundamental approaches for programming ICs during production: In-System Programming (ISP) and Off-Line (or Socket) Programming. The choice impacts production speed, quality control, and hardware investment.

Off-Line programming involves placing the unmounted, individual chip into a dedicated programming socket on a specialized programming machine—either a manual programmer or a fully automated system.

The primary drawback is the logistical step of handling the chips (picking and placing) before they are mounted to the PCB, requiring additional automation hardware.

ISP programs the IC after it has been soldered onto the Printed Circuit Board (PCB). The programming signal is sent through dedicated headers or test points on the board, using the chip's final application connections.

ISP is generally slower than Off-Line programming because the signal integrity is impacted by the entire PCB trace length, potentially limiting the programming clock speed. This method is often unsuitable for gigabyte-scale, high-speed memory devices used in high-volume production due to time constraints.

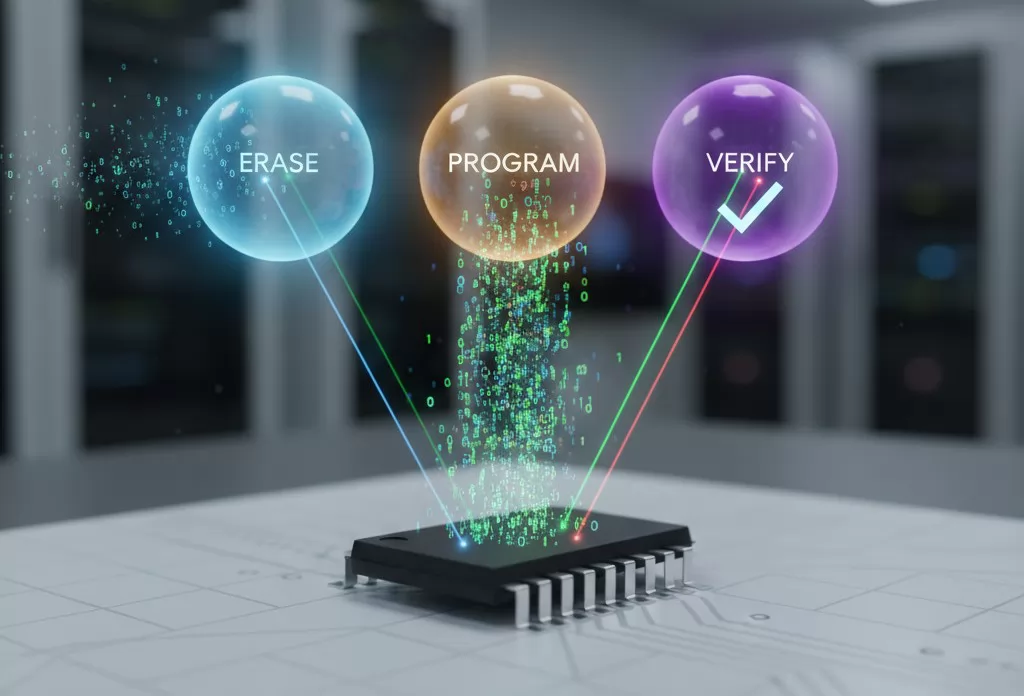

Regardless of whether off-line or in-system programming is used, the fundamental sequence of operations applied to the non-volatile memory of the IC follows a rigorous, multi-step workflow. Adhering to this workflow is essential for guaranteeing data integrity and device reliability.

The standard programming cycle can be broken down into three critical phases:

Before new data can be written, the memory block must be cleaned of any previous content. The Erase operation sets all bits within the designated memory area to a default state (usually all '1's, depending on the memory technology). For Flash memory, this is typically done on a block-by-block basis. Improper or incomplete erasing is a common cause of programming failure.

The Programming phase involves physically writing the target data file (the firmware or configuration bitstream) onto the chip's memory cells. This requires the programming hardware to communicate with the IC using its specific protocol (e.g., UFS, SPI, JTAG) and applying precise voltages to change the state of the memory cells. This is often the most time-consuming step, especially for high-density memory devices.

The Verification step is arguably the most critical for quality control. Immediately after writing, the programmer reads back the entire contents of the memory and compares it, bit-for-bit, against the original source data file. If even a single bit differs, the device fails the process and is marked as defective. This step ensures the program was written correctly and provides confidence in the final product's functionality.

In addition to the core stages, programmers often perform specialized operations:

The choice of programming equipment depends heavily on the production volume, the complexity of the IC packages, and the desired level of labor efficiency. IC programming equipment ranges from simple desktop units to high-throughput, fully automated machinery.

Manual programmers are desktop devices where an operator must physically place each IC into a socket, initiate the programming cycle, and remove the device once complete.

An Automated Programming System (APS), such as the advanced platforms offered by VeloMax, is designed for high-volume manufacturing. These systems integrate robotic handling, multiple parallel programming sites (gang programming), and sophisticated device management software.

For industrial B2B environments that manufacture consumer electronics, automotive components, or enterprise storage, the investment in an APS is justified by the requirement for flawless execution and unmatched speed to keep up with competitive market demands.

The continuous push for smaller, faster, and higher-capacity memory—driven by applications like electric vehicles (EVs), AI hardware, and flagship consumer electronics—introduces significant technical hurdles in the manufacturing process, particularly during programming.

Modern embedded memory standards like UFS (Universal Flash Storage) and high-density eMMC (embedded MultiMediaCard) often require transferring several gigabytes of data per device. If the programming process takes too long, it creates a severe production bottleneck.

UFS and eMMC use highly complex serial and parallel protocols (often requiring multiple data lanes) to achieve their high transfer rates. Programming solutions must handle:

ICs are continuously shrinking into smaller form factors, such as BGA (Ball Grid Array) packages, which are notoriously difficult to handle accurately.

Overcoming these challenges requires specialized, high-speed programming hardware built with robust design principles focused on achieving AeroSpeed performance and data integrity assurance at the gigabyte scale.

Choosing the correct IC programming solution is a strategic investment that directly impacts manufacturing throughput, quality assurance, and long-term operating costs. Technical managers must evaluate several critical factors beyond the initial price point.

A programming solution must comprehensively support the current and future devices used by the manufacturer. This includes:

In high-volume manufacturing, the overall cycle time (or TAKT time) of the programmer is the single most important metric. Slow programming creates bottlenecks that necessitate additional equipment or extended working hours.

Programming errors are costly. A superior solution must guarantee the highest level of programming accuracy:

For industrial-scale applications, the solution should integrate easily into existing production lines and offer scalability.

Here is the content for the ninth and final section: "Future Trends: Speed, Automation, and AI Integration."

The IC programming industry is not static; it is rapidly evolving to meet the demands of emerging technologies like autonomous driving, 5G infrastructure, and generative AI hardware. The future of programming is defined by increasing data volume, greater automation, and the integration of smart technologies.

As memory densities continue to rise (pushing into terabit capacities) and new protocols are standardized, the absolute programming speed will remain the primary competitive differentiator. Solutions must evolve past current bottlenecks.

The goal is to remove human intervention entirely from the programming and handling cycle, achieving "lights-out" manufacturing.

The next generation of programmers will incorporate AI and machine learning to optimize the entire process.

The future of IC programming is focused on delivering speed and precision, transforming what was once a bottleneck into a hyper-efficient, intelligent process point capable of meeting the demands of the next technological era.

Discover this amazing content and share it with your network!

Your Name*

Your Email*

*We respect your confidentiality and all information are protected.